In the history of humankind, art has been used as a medium for activism to effect change in society. And in a time when young people are finding creative forms of protest and avenues to champion various causes, you might be interested in learning how the surfaces of auto-rickshaws in Pakistan are being used as art canvases to channel messages of peace, tolerance and interfaith harmony. The ensuing conversation was with Syed Ali Abbass Zaidi, Founder of HIVE Pakistan and Pakistan Youth Alliance.

Tell us about life growing up in Pakistan and some of the experiences that led you on the path of youth activism?

As a 90’s kid who grew up witnessing the aftermath of both the Afghan Jihad as well as the War on Terror in the streets of Pakistan, it would be safe to say that the Pakistan in which I grew up was very different from the Pakistan of my parents. Since I was brought up in an environment where the concept of armed Jihad was glorified, it should not be surprising to hear that I, too, wanted to join the armed forces only so I could bomb India and liberate Kashmir. However, things took a massive turn with the emergence of the internet, a digital revolution that removed all the barriers that once existed between the people. As a result, I started interacting with people from all over the world, reading online articles and newspapers, eventually resulting in a major shift in my thought process. Pakistan was going through a tragic time then, with bombs going off in every city and targeted faith-based assassinations on the rise. I initially felt helpless but later converted the helplessness into something that I could give back to the country that made me the man I was. So much was being done to counter the terrorist threat, but no one was working to counter extremism in the realm of ideas. And that was how I found my calling; I knew this was something I could and must do. Since then, the journey has been long and treacherous, with moments of pride and success. Some of my close friends and fellow comrades were assassinated. I was in the dark. But then I thought, “As long as I live, why not make it a point to be a light that shines in the darkness?”

The Peace Rickshaws Project uses art to spread the message of peace, tolerance and interfaith harmony in Pakistan. Why art?

I believe the power of art transcends all borders and barriers of hate. It transcends our own self- interests and relates to the world with more integrity. History bears witness to how some of the greatest conflicts were resolved through art. We have examples where artists from both sides of the border, through their art and talent, brought down the barriers of hatred that existed between India and Pakistan. For example, in the 90’s when the relations between India and Pakistan were at their worst, Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan toured India and made the Indian public fall in love with his classical singing. Similarly, in the aftermath of the barbaric suicide attack in Sehwan Sharif in 2017, Sheema Kermani appeared at the shrine of Sehwan and performed dhamal. Her defiance through her art showed the whole world that nobody can stop dance. So, I believe art has the power to touch your soul, which is why we are using this as a medium to spread our message. Furthermore, art has great conversational power. It creates a space for dialogue and introspection. It can carry messages that otherwise may come across as radical.

Why rickshaws?

It is common in Pakistan to see buses and trucks adorned with beautiful images, paintings or stickers. Rickshaws, which are popular among commuters, did not receive the same artistic attention but instead, their bodies were being used as canvases to spread hatred against the United States and to support violent conflict with India and Afghanistan. We decided to use this same medium to preach peace and religious tolerance.

Workshops were organized to solicit inputs from the local youth, and we came up with slogans that promoted peace and eschewed violence and intolerance, especially among young people. We started off by decorating a few rickshaws in the Pakistani capital of Karachi. We have since then increased the fleet of rickshaws that market peace slogans. I am glad we got young people to actively participate in this by engaging their artistic side. They feel they are a part of the solution, and so do the rickshaw drivers who bought into our idea.

Through the movements and projects that you have initiated, you have presented counter-narratives to extremism and worked to de-radicalize local youth. What are some of the achievements you can point to?

Pakistan is a polarized society. It is a society where a security guard becomes a hero by killing someone he is supposed to be protecting. In such a society, religious hatred is rife and understandably so. This is because many people grow up learning from a curriculum that demonizes other religious groups, and they spend their lives avoiding any interactions with people with differing beliefs. And that way, the hatred festers.

Through our work, we have been able to bridge some of these gaps that exist between people. Our workshops, training sessions, focused group discussions and interfaith dialogues bring together people from different religious and ethnic backgrounds including Hindus, Shias, Ahmedis and so on: people who have been taught to hate each other. One of our achievements would be bringing these people together at a single table, where they can talk, share ideas, break stereotypes and engage in healthy dialogue.

Is there a particular story worth celebrating?

In December 2016, we brought together Pakistanis belonging to ten different religious schools of thought under one roof to take part in a “Shoot a mannequin challenge,” which was quite trendy on social media at the time. Through this challenge, various people got to know about some indigenous religious groups that exist in Pakistan, something they weren’t aware of before this exercise. One such religious group was the Persian-originated faith, Baha’i. Since then, the Baha’i community of Pakistan regularly attend our events and invite us to their festivals and religious gatherings. If we must celebrate one story, it would be the fact that our workshops and events are not just highlighting the pluralistic side of Pakistan but are also providing platforms to different religious groups to join hands and collaborate for a greater cause.

What best practices from the field of GCED do you apply specifically to attain the goals of the project?

I believe extremism is a domain of behaviour. It is a response to a score of push-pull factors that make you think you have a way to navigate through the contradictions of life and the world. By using the behavioural aspects and concepts of GCED we have developed programs that counter extremist thoughts and actions. Most of the extremists are suffering from dissonance, group bias, psychological and interpretative hurdles and, with that, the cognitive aspects of GCED can help. For the Peace Rickshaws project, we studied best practices in both the behavioural and cognitive competencies under GCED and went on to incorporate those in our program.

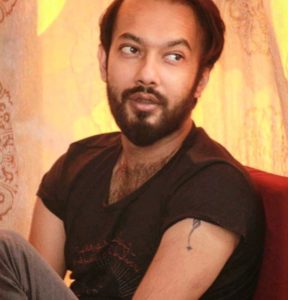

About Syed Ali Abbass Zaidi

About Syed Ali Abbass Zaidi

Mr. Syed Ali Abbass Zaidi is the Founder of the Pakistan Youth Alliance “Peace Rickshaws” Project. Over the years he has led several movements and projects to present counter-narratives to extremism, to deradicalize youth and to engage diverse communities in Pakistan in a collective dialogue for tolerance. In 2012, he created the Peace Rickshaws Project as an effective way to initiate conversations on peace and has since been spearheading the initiative. Through the Peace Rickshaws Project, Pakistan Youth Alliance uses the canvas of auto-rickshaws and medium of pop-art to relay messages of peace, tolerance and interfaith harmony in Pakistan.