An interview with Professor Helen Spencer-Oatey, Professor at the Centre for Applied Linguistics The University of Warwick.

There seems to be a focus on on-boarding programs as the surest way of embedding intercultural competence in students in higher education. Is this a foolproof method or should we begin to look internally for other ways students can develop these skills?

There seems to be a focus on on-boarding programs as the surest way of embedding intercultural competence in students in higher education. Is this a foolproof method or should we begin to look internally for other ways students can develop these skills?

In my experience, most on-boarding/induction programs are aimed at helping students adapt to the new environment of the university. All students – domestic as well as international – need to adjust to many new things at university, because the way of life (both social and academic) is usually very different from what they have been used to. The focus of on-boarding programs is thus often on introducing students to the way things work at the university and giving them opportunities to meet people and make new friends. This is all extremely important but is not synonymous with the development of intercultural competence. Of course, learning to adapt is one aspect of intercultural competence, but there are many other facets that underpin the ability to work and communicate well across cultures and build strong relationships. Those capabilities take time to develop and cannot be ‘trained’ in one or two weeks. They need gradual step-by-step fostering over the full degree program.

It is quite common to have universities boast about their internationalisation strategies. But there is the fear that they might just be interested in the numbers. How would you reckon these institutions capitalise on their internationalisation strategies to enhance ICC among students?

Yes, a few years ago a professor of higher education, Peter Scott, argued in a newspaper article that “There is an urgent need to reset the compass of internationalisation, to steer towards the good and away from the ugly.” He identified the pressure to recruit international students as one of the ‘bad’ aspects, and the potential to transform the lives of students as one of the good. Unfortunately, league tables and associated university rankings detract from the ‘good’, as numbers are easy to count and rank. The fact that international students frequently refer to league tables when deciding which universities to apply for worsens the situation.

Nevertheless, there is a growing awareness, at least among some universities, that internationalisation should mean more than recruitment of diverse staff and students and increase in the amount of mobility. While those are important pre-requisites, they are not an end in themselves. Universities need to be on a trajectory of internationalisation, which moves from the stage of compositional internationalisation to community internationalisation and to competency internationalisation. This costs time, effort and money, and the involvement of all concerned (students, academics and professional services staff), but the end goals makes that truly worthwhile.

And I believe this is where your university’s tool, the Global Education Profiler comes in handy. Could you tell us more about this?

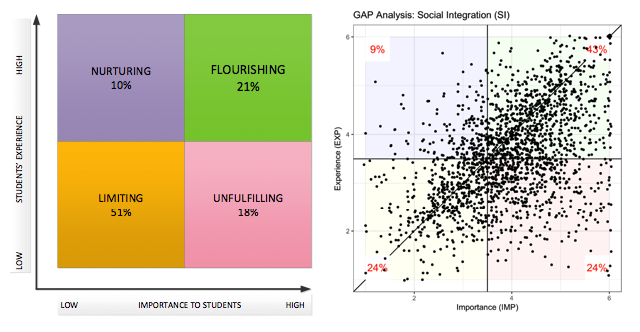

The Global Education Profiler (GEP) is a diagnostic tool that helps university management identify what kind of global learning environment their students and staff value and are experiencing. There are two complementary versions: one for students and one for staff, both academic and professional services. The GEP is very different from traditional measures of internationalisation and has yielded important findings. For students, it probes 5 facets: social integration, academic integration, foreign language learning skills, communication skills, and global opportunities and support. Respondents rate items probing these facets in two ways: ‘importance to me’ and ‘my actual experience’. We report the findings in multiple ways; notably in terms of size of gap between importance and experience ratings, a matrix of proportions in the different quadrants, and a scatterplot distribution (see figures below).

This enables senior managers to plan and prioritise their efforts. For example, if many students’ scores fall in the ‘Limiting quadrant’ (i.e. the facet is not important to them and they are not achieving it), they will need very different handling from students who fall in the ‘Unfulfilling quadrant’ (i.e. the facet is important to them but they are not experiencing it). It is also interesting to note that students close to the diagonal of the matrix would normally count as satisfied students, but many of these could be in the Limiting quadrant – in other words, indicating that they do not care about internationalisation.

The GEP can also be used for individualised feedback to student, with personalised suggestions for improving. Moreover, there is a version for staff, since intercultural competence is an issue that is relevant to everyone. More details, including an interactive dashboard and a number of papers, can be found on our GlobalPeople website, in both the sections For HE Institutions and Knowledge Exchange.

When it comes to the teaching of the subject, would you say the current methods being used are effective to prepare students for the cross-cultural world that awaits them after school?

I would think that there’s a lot of variation among universities. There seem to be many initiatives to promote social integration, but data from the GEP suggest (as can be seen, for example, from the scatterplot above which shows domestic student data) that there is still a long way to go. A particularly challenging issue is how to interest and motivate those students who really don’t care about intercultural interaction and global skills at all. We need to be more imaginative in relation to that. There is also the question of using the regular classroom more for fostering intercultural competence. There are numerous opportunities for that, not just in terms of the curriculum but also with regard to classroom interaction and the development of intercultural communication skills. This requires training for the academic staff, though, and I think it is something that really needs more attention.

Apart from the GEP which you mentioned earlier, what other tools are being developed by your institution to give students a better appreciation of intercultural communication/competence?

We have a number of tools on our GlobalPeople website, including the 3R reflective tool and the 4S stretch tool, both of which are very popular.

We have just launched our Working in Groups online/blended learning course. Its aim is to help people work more effectively in diverse groups and teams (e.g. handle different working patterns and communication preferences). It was developed with and for students and it explores four core components of team communication and related intercultural factors. Each component includes:

- mini case studies

- interactive tasks designed around authentic examples of student teamwork

- video clips of students’ reflections

- a section on research perspectives

A key feature is reflection, because reflection helps turn an experience into learning. The course is available by licence and includes an Instructor’s Guide when multiple licences are purchased. An information leaflet and a course sample are available on the GlobalPeople website.

Professor Helen Spencer-Oatey (LinkedIn) was interviewed by Tawakalitu Braimah.